Lockdown season is upon us again (here too, alas). I don’t think I know anyone who actively enjoys life under quarantine. But some people seem to have a harder time with it than others, and it’s interesting to think about why that is.

One obvious thought is that homebodies who dislike socializing in big groups should be doing pretty OK, and maybe even better than usual. This is their dream lifestyle, right? And not only do they get to enjoy it for weeks on end, they also never have to feel bad about skipping a baby shower or birthday party, since those aren’t happening. On the other hand, this theory predicts a lot of miserable extraverts, cut off from their source of deepest joy. Maybe trying to fill that hole with Zoom cocktail hours, only to find that it’s so hard to be the center of attention with all these other faces on the screen.

It’s a plausible theory, and one that has a lot of buy-in from the media and internet culture. E.g.:

So I found it interesting to learn that this theory is apparently false. Not only are introverts failing to live their best-ever lives under lockdown, they seem to be doing worse than extraverts along important mental health axes.

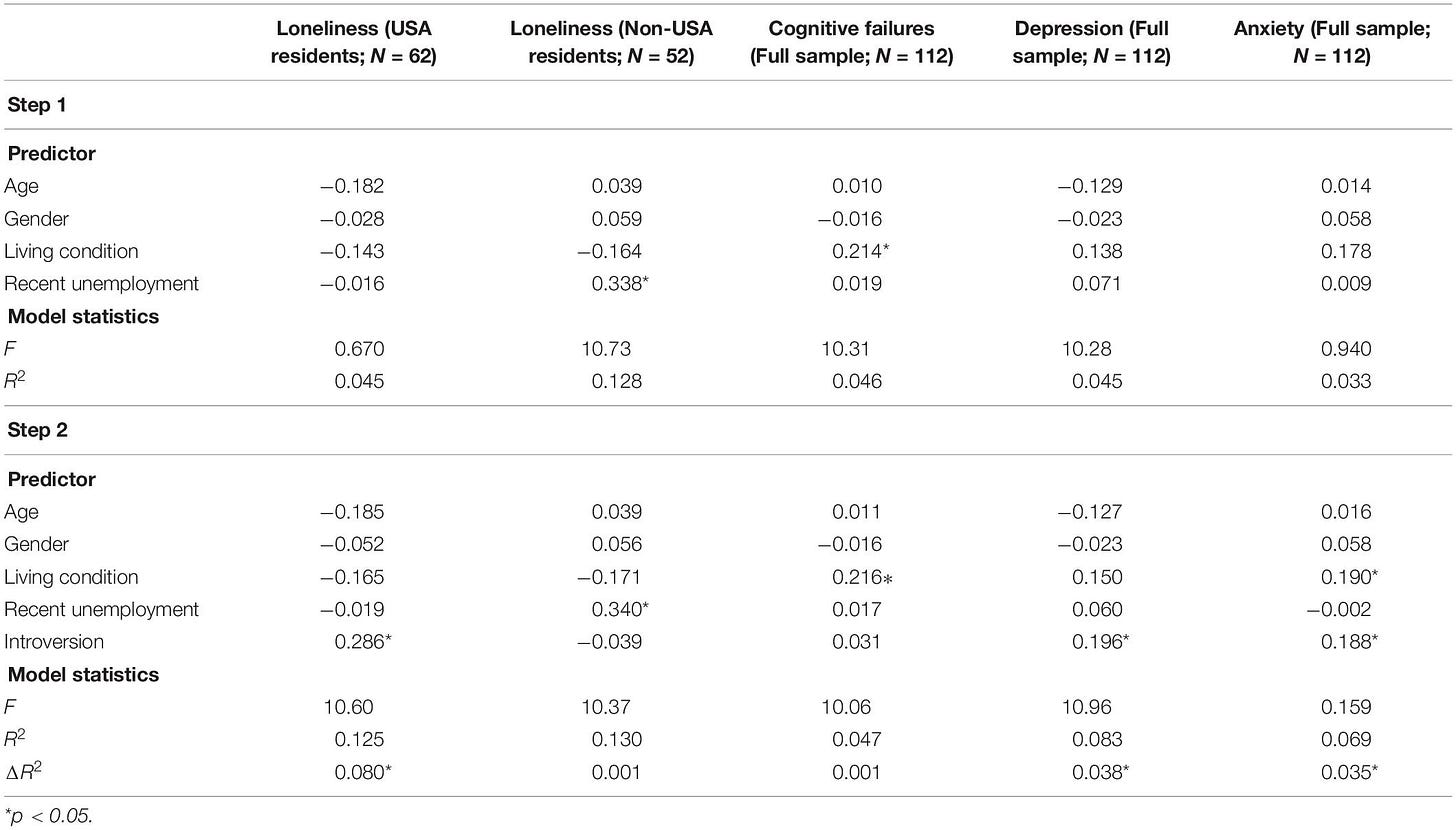

This paper by Wei in Frontiers of Psychology, for example, finds that introversion predicts greater loneliness, anxiety and depression as a result of covid-related changes in circumstances. This Forbes piece summarizes different research coming to a similar conclusion (although there seems to be no peer-reviewed publication here yet). The effect sizes in the Frontiers paper are modest but not tiny. Here’s the main table of results if you’d like to get your nerd on.

So if introverts really are doing worse, why would that be? As Wei points out, the study doesn’t try to disentangle the distress caused by lockdowns in particular from the broader mental health effects of the pandemic. And introverts are evidently known to experience more covid-related worry and fear. So it’s possible that extraverts are more unhappy than introverts about being stuck at home, but introverts are disproportionately more unhappy than extraverts about the state of the world in general. Some other likely factors: introverts tend to experience more intense negative emotions, they’re more susceptible to mental health problems, and they have a harder time adjusting to disruptions in their lives.

This makes a certain amount of sense of my experiences. I score as moderately extraverted on Big Five-type tests, and I do very much miss seeing my friends, but on the whole my mental health hasn’t suffered tremendously during the pandemic. And I live with an introvert for whom this has been a rockier road, mostly, I think it’s fair to say, on account of worry rather than social deprivation.

Wait, but didn’t Wei find that introverts are also likely to feel more lonely? That seems like it’s due specifically to quarantine isolation rather than disease fears, right? Yes, that was the finding—but unlike the anxiety and depression results, the loneliness effect only appeared for US respondents. The correlation actually went (non-significantly) in the other direction for folks in other countries. So it might be noise, or it might be that American introverts were lonelier because our lockdowns were more isolating in some way.

I’d like to hear about your experiences and what you make of these data. (You too, introverts! Quit lurking!)

I tend to agree with this direct correlation to worry and our reaction to the pandemic. We may say we are totally fine being on our own, but this is a prolonged period. I for one find myself saying things like I can find a thousand things to do, but then I buckle at times. It's very much like a grief process being separated from family so much. Our work family can only fill a small part of the void. Although work right now is risky, it does bring the human connection.

Bill, I'm compelled to complain about the reliance on the introvert/extrovert and Big Five personality types literature. Setting aside issues of reproducibility -- which is itself a pretty serious problem -- there are various conceptual and methodological issues with the ways these categories are defined and operationalized. I don't mean to say that there is no such thing as personality or character traits, but I'm wary of treating these theoretical constructs of psychology as real categories. My worry is amplified further by Ian Hacking's idea of looping kinds, where just embracing the psychological classification can shape a person's sense of self in such a way as to make them fit the classification. Does one need to rely on work in personality psychology to make sense of one's experience during the pandemic? What does it add really?